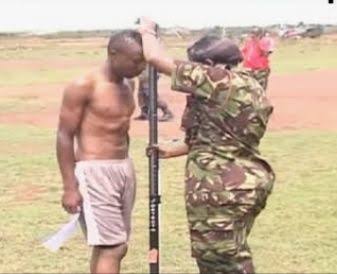

Kenya’s policing structure has entered a new phase following a landmark judgment that reshapes the balance of power between the National Police Service Commission (NPSC) and the Inspector General of Police. The Employment and Labour Relations Court, in a decision delivered on October 30, 2025, by Justice Hellen Wasilwa, declared that the NPSC’s recent recruitment exercise was unconstitutional. The ruling followed a petition filed by former legislator John Harun Mwau, who challenged the legality of a recruitment notice issued under Legal Notice No. 159 of September 19, 2025, in which the commission had announced plans to recruit 10,000 police constables.

Justice Wasilwa, who had earlier suspended the exercise through interim orders on October 2, found that the NPSC had overstepped its constitutional mandate. In her judgment, she stated:

“The National Police Service Commission is not a national security organ under Article 239 of the Constitution and therefore lacks the authority to recruit, train, or discipline police officers.”

Those powers, she ruled, belong exclusively to the Inspector General (IG) and the National Police Service (NPS). Consequently, she declared the entire recruitment process null and void, effectively barring the NPSC from conducting any future police recruitments.

The court further directed Parliament and the Ministry of Interior to harmonize the National Police Service Act and the NPSC Act with the Constitution so that their provisions reflect the correct interpretation of roles and powers within the police service. The decision has once again brought to the surface a long-running power struggle between the two institutions — the NPSC, which was created to oversee human resource management in the police service, and the office of the Inspector General, which is charged with operational command.

Why Babu Owino Can Never Be Raila Odinga

This conflict is not new. Since the promulgation of the 2010 Constitution, Kenya has grappled with defining the boundary between police oversight and command authority. The NPSC has often maintained that Article 246 gives it power to recruit and promote officers as part of its human resource management role. However, the Inspector General, under Article 245, enjoys operational independence, including the authority to control and direct the work of the police service. This overlapping interpretation of the law has led to frequent institutional friction and confusion.

During the hearing, the Attorney General and Inspector General Douglas Kanja supported the petition, arguing that the NPSC had usurped powers constitutionally reserved for the IG. They warned that continued encroachment by the commission risked weakening the command structure of the police service and creating accountability gaps within the ranks. The court agreed with this position, finding that recruitment falls under the IG’s administrative control, since it directly influences the composition and effectiveness of the police force.

However, the judgment has also drawn criticism from governance experts and civil society groups. Some argue that stripping the NPSC of recruitment powers undermines civilian oversight — one of the key principles that informed police reforms after 2010. They fear that leaving recruitment solely to the Inspector General could open the door to political influence, favoritism, and corruption in hiring processes. Others warn that without the commission’s involvement, transparency and merit-based selection could be compromised, eroding public trust in the police service.

KMTC Graduates Struggle With Employment

Supporters of the ruling, on the other hand, argue that it restores clarity and discipline to the command chain. They contend that recruitment, being a fundamental aspect of operational readiness, should remain under the IG’s purview, as the head of the national police. According to them, the NPSC’s proper role is to handle employment matters for civilian staff within the service, as well as to ensure fair management of welfare, promotions, and disciplinary appeals — not to interfere in operational matters like recruitment and deployment.

Legal scholars now emphasize the need for Parliament to urgently review the relevant laws to align them with the Constitution and this new interpretation. They also recommend the establishment of clear oversight frameworks to ensure that the Inspector General’s recruitment processes remain transparent and accountable, even without direct NPSC involvement.

The October 2025 ruling could mark a turning point in Kenya’s decade-long effort to reform its policing institutions. It reaffirms the operational independence of the Inspector General while redefining the scope of civilian oversight in security matters. Yet it also raises fundamental questions about checks and balances: how to ensure accountability within a police force that now has greater autonomy, and how to prevent concentration of power in one office.

As Kenya prepares for future recruitment drives, all eyes will be on the Inspector General to demonstrate that this newfound authority can be exercised responsibly and fairly. The NPSC, meanwhile, must adapt to a new, more limited role — focusing on policy, welfare, and administrative management rather than direct control of police personnel. Whether this ruling leads to a more efficient and professional police service or sparks fresh institutional tension will depend on how faithfully both offices implement the court’s directive. What is certain is that Justice Wasilwa’s ruling has redefined Kenya’s policing landscape, closing one chapter of bureaucratic conflict while opening another of constitutional accountability.

“The October 2025 ruling redefines Kenya’s policing landscape, closing one chapter of bureaucratic conflict while opening another of constitutional accountability.”

This article was prepared by the Ramsey Focus Analysis Desk, based on verified reports, independent analysis, and insights to ensure balanced coverage.

6 Responses