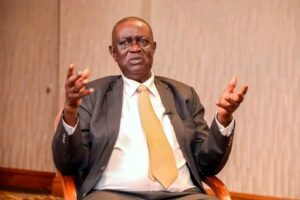

The Shocking Story Behind Justice Majanja Choice Never to Marry and Inheritance Conflict

The death of a public figure often reveals more than their professional legacy. It exposes family histories, unresolved trauma, and legal questions that society prefers to ignore until conflict forces them into the open. The inheritance dispute surrounding the late Justice David Majanja has become one such moment.

What began as a quiet legal process has evolved into a national conversation touching on childhood trauma, family estrangement, marriage conflicts, and the limits of testamentary freedom under Kenyan law. Beneath the surface accusations of greed and entitlement lies a deeper question. Should the law blindly obey a will, or must courts interrogate the circumstances under which it was made?

Public discourse surrounding this case has largely focused on the contested will and the perception that siblings are attempting to override the deceased wishes. However, many people who claim familiarity with Justice Majanja’s personal history argue that the will cannot be understood in isolation from his life story. Human beings do not draft wills in emotional vacuums. Personal history, trauma, loyalty, resentment, and trust all shape testamentary decisions. Ignoring these factors risks turning the law into a blunt instrument rather than a tool for justice.

One recurring theme in discussions about Justice Majanja is childhood trauma. Trauma in early life often leaves invisible scars that influence adult behavior, relationships, and life choices. Accounts circulating in the public domain suggest that Majanja grew up in a deeply unstable family environment marked by conflict and emotional pain. The alleged death of his mother under distressing circumstances and the claim that he was the first to encounter her body are often cited as formative experiences.

Psychological research consistently shows that children who experience sudden parental loss, especially in traumatic conditions, are more likely to develop emotional withdrawal, distrust of intimate relationships, and a heightened need for control in adulthood. This context is often raised when explaining why Justice Majanja never married. Marriage is not simply a social milestone. It requires emotional vulnerability, trust, and the willingness to form permanent bonds.

For individuals shaped by early abandonment or family instability, marriage can represent risk rather than comfort. Some people cope by avoiding long term romantic commitments altogether, choosing instead to invest in siblings or professional life where loyalty feels safer and more predictable. The absence of marriage in inheritance cases is legally significant. In Kenya, spouses enjoy strong protection under succession law.

Where a deceased person leaves a surviving spouse, courts are often reluctant to interfere with testamentary intentions that benefit that spouse. However, where there is no spouse or biological children, disputes become more complex. The court must then balance testamentary freedom against the rights of dependents, siblings, and parents who may have relied on the deceased for support.

Marriage conflicts also play a critical role in inheritance disputes, even indirectly. When a parent remarries, especially after a turbulent separation, loyalties within the family often fracture. Blended families create emotional fault lines that resurface during succession. Children from earlier relationships may feel displaced, while stepchildren may seek validation and recognition.

These emotional dynamics frequently manifest as legal battles over property rather than honest conversations about belonging. In the Majanja case, public narratives describe long standing estrangement between father and biological children, followed by closer alignment with a later partner and her child. Whether or not these claims withstand legal scrutiny, they raise an important legal question.

Can a will be valid if it appears to contradict the deceased established relationships and patterns of support? Kenyan law does not treat a will as sacred simply because it exists. Courts are empowered to examine both its formal validity and its substantive fairness.

Under the Law of Succession Act, a will must meet certain formal requirements to be valid. It must be made voluntarily, by a person of sound mind, and without undue influence. If any of these elements are missing, a court may declare the will invalid. Beyond formal validity, the Act introduces the concept of reasonable provision for dependents.

This means that even a valid will can be altered by the court if it fails to provide adequately for individuals who depended on the deceased during their lifetime. This is where many inheritance disputes turn contentious. Some people believe that a will represents absolute freedom and that courts should simply obey it.

In reality, testamentary freedom is not absolute. It exists within a legal framework designed to prevent injustice. Courts must consider whether the deceased was under pressure, manipulation, or emotional vulnerability when making the will. Where a will fails these tests, intervention is not defiance of the deceased wishes. It is protection of justice.

“Courts must respect wills, but justice demands they examine the circumstances behind them.”

This article was prepared by the Ramsey Focus Analysis Desk, based on verified reports, independent analysis, and insights to ensure balanced coverage.

For statutory context, see the

Law of Succession Act of Kenya

.