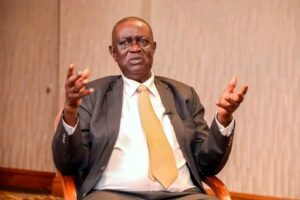

The Cost of Being on the Wrong Side of Power: Ho Ferdinand Waititu’s Politics Caught Up With Him and Ksh131 Million Forfeiture

The recent court ruling requiring former Kiambu Governor Ferdinand Waititu to forfeit assets worth Ksh131 million has sparked renewed discussion about accountability, political loyalty, and corruption in Kenya.

While the decision marks a tangible victory for the State, it also exposes the limitations of asset recovery in politically charged cases. The disparity between the initial Ksh1.9 billion claim and the final forfeiture highlights both legal and political complexities.

The assets to be surrendered include two parcels of land valued at Ksh32 million, a Caterpillar construction tractor worth Ksh11 million, and two vehicles priced at Ksh600,000 each.

The Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) linked these assets to suspected illicit dealings during Waititu’s tenure as Kabete MP from 2015 to 2017 and as Kiambu Governor from 2017 to 2020. These periods coincide with increased access to public resources, creating conditions prone to corruption.

Legally, the case illustrates the careful balance courts strike between protecting property rights and enabling the State to recover stolen public funds.

Civil asset recovery requires proof on a balance of probabilities, unlike criminal prosecution, which demands evidence beyond reasonable doubt. The limited forfeiture demonstrates the judiciary’s insistence on rigorous evidence linking assets directly to misconduct.

Politically, the ruling underscores the risks associated with aligning with the wrong faction in a country where power shifts frequently. Waititu’s previous impeachment during former President Uhuru Kenyatta’s administration and his later support for opposition interests illustrate how political misalignment can intensify scrutiny and legal vulnerability. Observers argue that had he remained loyal to the ruling party, he might have avoided the full extent of the legal challenges he now faces.

The decision also serves as a reminder that corruption accountability is not solely about money. While Ksh131 million represents a significant recovery, the remaining disputed wealth underscores the difficulty of tracing complex financial arrangements and ownership structures. Proxy holdings, staggered transactions, and opaque corporate entities often shield politically exposed individuals from full legal consequences.

The ruling highlights the broader challenges within Kenya’s anti-corruption architecture. Agencies like the EACC rely on detailed forensic investigations and cross-agency cooperation to establish clear ownership of assets.

Any gaps in evidence can result in scaled-down recoveries, as illustrated by the difference between the original Ksh1.9 billion claim and the final forfeiture. Political context often influences the pace and outcome of these proceedings, reflecting the intertwined nature of law and politics.

Economically, the recovered assets can provide tangible benefits for public finances, but they cannot fully compensate for the broader fiscal damage caused by corruption. Misappropriation of public funds inflates project costs, stalls development, and erodes citizen trust in institutions. Recovering Ksh131 million is a step toward restitution, yet the systemic costs of corruption remain largely unaddressed.

From a societal perspective, partial recoveries may shape public perception more than they resolve structural problems. Kenyans often interpret such rulings as evidence of selective accountability, where politically connected individuals retain most of their wealth. This perception undermines the deterrent effect of anti-corruption measures and highlights the need for consistent, transparent enforcement.

Waititu ruling provides both a precedent and a warning. Courts will continue to scrutinize the scope of asset recovery claims, requiring robust evidence for each contested asset. Anti-corruption agencies must enhance investigative rigor, trace financial flows more effectively, and anticipate political pushback. Only a combination of legal precision and political will can deliver meaningful accountability.

“In a country where politics and power are inseparable, Ferdinand Waititu’s case shows that the wrong alliance can have lasting legal and financial consequences.”

This article was prepared by the Ramsey Focus Analysis Desk, based on verified reports, independent analysis, and insights to ensure balanced coverage.